ADA Web Site Compliance Still Not a Thing

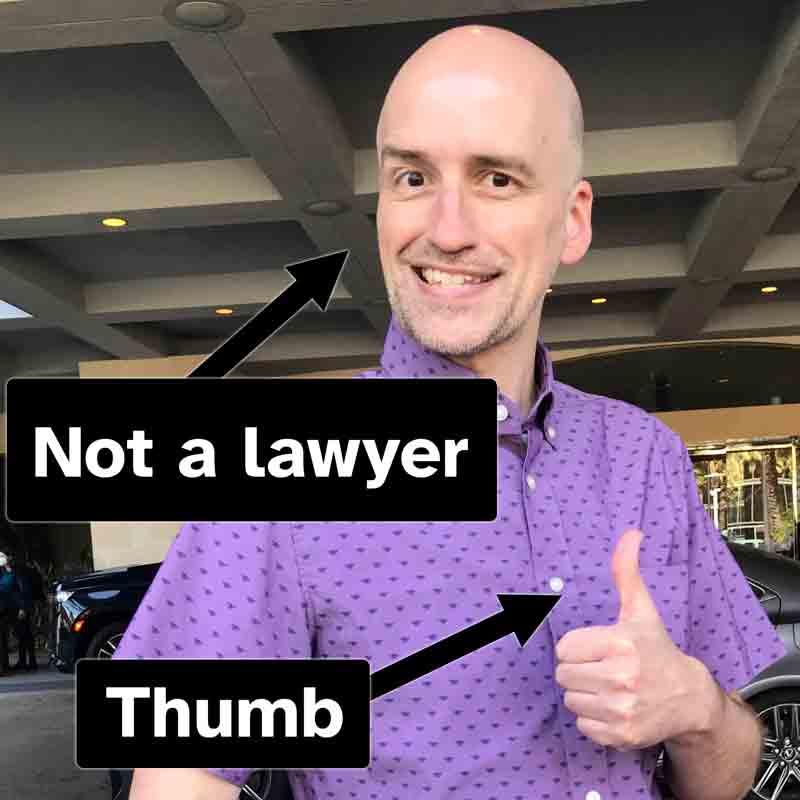

Who has two thumbs and is not a lawyer?

For years I have worked with clients who refer to digital/web accessibility as ADA work. They have talked about ADA testers, ADA reviews, ADA requirements, and so on. My efforts to correct that have been ruined by overlay vendors who promise ADA compliance in their marketing materials.

Except the ADA is silent about the web.

Mini-Timeline

There is a good reason why the ADA is silent about the web. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law on 26 July 1990. It borrowed from the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

The very first web browser, WorldWideWeb, which was created by the inventor of the web, was released on 25 December 1990. Five months after the ADA was made the law of the land (minus one day). You can still download it for NeXT systems from the evolt.org browser archive.

The ADA does not talk about the web because the web did not exist yet.

Other U.S. Laws

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 extended civil rights to people with disabilities as well as requiring reasonable accommodations as needed. However, this applies to federal agencies, though it includes organizations that receive federal funding. Generally this covers federal employment as well as access to federal programs. It is also not focused on digital accessibility given its age. It is also not part of the ADA.

In 1986, Section 508 amended the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, failed, and then came back in 1998 with enforceable requirements. Though it only applies to the government (procurement, mostly). In 2017, the 508 Refresh aligned Section 508 with WCAG 2.0 at Level AA and, most importantly, is still not part of ADA. Nor is Section 255 of the Communications Act, which I am ignoring here owing to its focus on telephony, though it is often referenced alongside Section 508.

The 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act (CVAA), as its name implies, is far more current. Signed into law on 8 October 2010, three years after the iPhone debuted, and covers communications access and media (video) accessibility. Importantly, it has no technical guidelines but is generally open-ended. It is also not part of the ADA.

The Air Carrier Access Act of 1986 (ACAA) was updated in 2013 to address not just bathrooms, service animals, and luggage, but also web sites and kiosks. By December 2016, the entirety of an airline site had to be accessible. The web sites and kiosks final rule cites WCAG 2.0 Level AA. This law is also not part of the ADA.

In fact, there are enough laws related to accessibility in general that the ADA web site has a disambiguation page.

Why Has the ADA Not Been Updated?

Momentum. As in, momentum to update the ADA had finally built up, then it was suddenly lost.

I am over-simplifying, of course, but I refer you to the opening statement of this post. I am not a lawyer; I am not a lawmaker. I am just a guy with a keyboard and some grump.

On 28 February 2022, 181 disability organizations wrote a Joint Letter to Enforce Accessibility Standards to the head of the US Department of Justice (DoJ) Civil Rights Division. The letter asked for enforceable online accessibility standards by the end of the current Administration

:

In 2016, the National Council on Disability (NCD) recommended that the Department of Justice issue a notice of proposed rulemaking that reinforces that the ADA applies to the internet. NCD also recommended that multiple agencies complete existing rulemakings and initiate new rulemakings on accessibility of various types of information and communication technology (ICT), including web content, applications, hardware, and software. The absence of digital accessibility regulations in the intervening time period has resulted in persistent exclusion of people with disabilities from digital spaces covered by the ADA.

What We Got Instead

On 18 March, the US Department of Justice put out a release, perhaps as a response to the open letter, titled Justice Department Issues Web Accessibility Guidance Under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

That release points to a resource at ADA.gov titled Guidance on Web Accessibility and the ADA. While the URL is beta-dot (suggesting it is temporary), it still demonstrates that the US Federal Government is taking a position on how WCAG and Section 508 (which incorporates WCAG 2.0) apply.

That position, however, is anemic.

It addresses state and local governments (Title II) with this conclusion:

For these reasons, the Department has consistently taken the position that the ADA’s requirements apply to all the services, programs, or activities of state and local governments, including those offered on the web.

It then addresses public-facing businesses (Title III) with this conclusion:

When you wander into the section How to Make Web Content Accessible to People with Disabilities, you are greeted with this:For these reasons, the Department has consistently taken the position that the ADA’s requirements apply to all the goods, services, privileges, or activities offered by public accommodations, including those offered on the web.

Businesses and state and local governments have flexibility in how they comply with the ADA’s general requirements of nondiscrimination and effective communication. But they must comply with the ADA’s requirements.

The Department of Justice does not have a regulation setting out detailed standards, but the Department’s longstanding interpretation of the general nondiscrimination and effective communication provisions applies to web accessibility.1

The DoJ confirms what we had already guessed by now — as a law it does not mandate WCAG. Certainly not with the word flexibility

for compliance.

While it cites WCAG and Section 508, the document never explicitly states which version of WCAG it considers appropriate. But since the document is essentially kicking this back to case law, we can look at those referenced in the press release for insight:

[T]he department recently entered into numerous settlements with businesses — including Hy-Vee, Inc., The Kroger Co., Meijer, Inc., and Rite Aid Corporation to ensure that websites for scheduling vaccine appointments are accessible.

Each of those settlement agreements explicitly identifies WCAG 2.1 Level AA.

A Tiny Concern

The document uses the word “overlay” once:

Checking for accessibility. Automated accessibility checkers and overlays that identify or fix problems with your website can be helpful tools, but like other automated tools such as spelling or grammar checkers, they need to be used carefully. A “clean” report does not necessarily mean everything is accessible. Also, a report that includes a few errors does not necessarily mean there are accessibility barriers. Pairing a manual check of a website with the use of automated checkers can give you a better sense of the accessibility of your website.

I don’t think the guidance means overlays in the context where I (and others) have repeatedly shown overlays to be ineffective. Given that overlays have lost cases for their clients, and in some cases are explicitly banned in settlements, the case law should continue to prove to be an effective bulwark against overlays as we in the industry know them.

What to Do?

If nothing else, this statement from the DoJ is the most visible support for WCAG 2.x and the ADA that practitioners have gotten. While explicit rules updates would be far better, we can at least show this to our clients as an example that the DoJ considers web sites beholden to the ADA. Even if the law itself still does not say so.

Remember, I have two thumbs and am not a lawyer.

Additional Reading

Other than the U.S. Access Board link, I am not linking posts or articles that regurgitate the Guidance and which offer no new insights. I have no interest in promoting the noise from agencies clamoring for clicks with quick takes.

- Department of Justice Issues Web Accessibility Guidance Under the ADA, U.S. Access Board, 21 March 2022

- The DOJ’s New Guidance Says Website Accessibility is an Enforcement Priority but Provides No New Legal Insights, Minh N. Vu, Seyfarth Shaw LLP, 21 March 2022

- DOJ’s Guidance on Web Accessibility and the ADA, William D. Goren, J.D., LL.M., LLC, 21 March 2022

- Why We Should Be Disappointed by DOJ’s Web Accessibility Guidance, Ken Nakata, Converge Accessibility, 22 March 2022

- DOJ Issues Website Accessibility Guidance—Key Questions Remain Unanswered, David Raizman at National Law Review, 23 March 2022

Update: 26 March 2022

It is now a week later and the big accessibility consultancies who have chosen to blog about this are mostly using it as I expected — indirectly stating you must hire them to meet the ADA, otherwise you could get sued. Few seem interested in pointing out how half-hearted an approach this was from DoJ. At some level this suggests the accessibility consultancies’ priority is not people, but revenue.

Update: 1 July 2022

It has been 10 years since the Department of Justice filed a biennial report on the federal government’s compliance with accessibility standards for information technology, a bipartisan group of concerned senators say. The reports are required by Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act.

They are required to issue a report every two years. The last report was delivered in 2012, and it looks the only other years covered were 2004, 2001, and 1999. The letter from seven senators to the Department of Justice outlines some of the last documented failings and asks questions about what to expect.

The concern here is that if the DoJ cannot follow its own reporting guidelines, it sends the wrong message to those hoping the DoJ will weigh in for other accessibility legal efforts.

Update: 1 October 2022

On Thursday, Senator Tammy Duckworth and Representative John Sarbanes introduced a new bill called Websites and Software Applications Accessibility Act (posted on each of their Congressional pages as an untagged PDF):

To establish uniform accessibility standards for websites and applications of employers, employment agencies, labor organizations, joint labor-management committees, public entities, public accommodations, testing entities, and commercial providers, and for other purposes.

Essentially it hopes to formalize web accessibility in law instead of relying on assorted rulings and DoJ statements. The bill also proposes that the regulations will be updated every three years.

Duckworth’s version is S.4998 is on Congress.gov, and Sarbanes’ version is listed as H.R.9021 on Congress.gov, though as of the morning of October 3 neither the summary nor full text is there for either. Update, October 24: the full text for each bill is now on the site, without a summary, as of the week of October 17 (I missed it while traveling).

At this point it is just a bill, and Congress may never take it up. It is good to see some potential movement on digital accessibility regardless, especially when jointly introduced in both houses. Ben Myers wades into the bill if you want a breakdown.

Remember that in February 2021, Ted Bud introduced H.R.1100 Online Accessibility Act (which also cited WCAG), where the last activity it had was adding a fourth co-sponsor in November 2021. It appears to have died in the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Commerce.

Update: 24 October 2022

Lainey Feingold also has a post, Proposed web and software accessibility legislation introduced in United States Congress, dated 9 October, which she updated yesterday to call out the fact the bill defines “accessible”.

ACCESSIBLE.— The term “accessible” or “accessibility”, used with respect to a website or application, means a perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust website or application that enables individuals with disabilities to access the same information as, to engage in the same interactions as, to communicate and to be understood as effectively as, and to enjoy the same services as are offered to, other individuals with the same privacy, same independence, and same ease of use as, individuals without disabilities.

You may recognize WCAG’s POUR acronym in there.

Update: 27 November 2022

The ADA site launched a new site, announced on 18 November, or eight months after the position statement on web accessibility that prompted this post. The DoJ posted its own copy of the release five days later.

The March guidance document also moved to a new URL. Sadly, the 301 redirect is broken so I updated all my links in this post. The old ADA site is still available at archive.ada.gov, which is where I am now pointing the PDF links from the DoJ statement on settlements.

If you find issues on the new ADA site (links, usability, WCAG violations, whatever), you can leave up to 2,500 characters of feedback on the site.

Update: 3 January 2023

With today wrapping up the 117th session of Congress, it seems unlikely Duckworth’s S.4998 or Sarbanes’ H.R.9021 Websites and Software Applications Accessibility Act is going anywhere.

While the bills may be re-introduced in the new Congress, Republican control of the House suggests a steeper climb to get any traction (assuming Republican votes are more consistent than the last few weeks of its only Speaker candidate failing to get support).

Duckworth’s bill was referred to the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions committee and netted five co-sponsors (all Democrats, all returning). Sarbanes’ bill was referred to the House Education and Labor committee and the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties. It netted nine co-sponsors (all Democrats, all but one returning, and one is a non-voting member).

Update: 27 October 2023

Still not a lawyer, so not attempting to keep this current with all the things that have been happening over the last ten months. However, I did want to add when Duckworth and Sarbanes re-introduced their bills but I was on the road, in other countries, and busy not updating this post.

Both Duckworth and Sarbanes announced their joint bill on 28 September. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey as co-sponsored when the Senate bill was introduced with Brian Schatz and Ron Wyden joining on 18 October. Congressman Pete Sessions co-sponsored the House bill and David Trone joined on 12 October (the house was unable to pass legislation at the time owing to lack of a Speaker).

The text of Duckworth’s S.2984 and Sarbanes’ H.R.5813 for the 118th session of Congress are online for your perusal. They are both still called Websites and Software Applications Accessibility Act of 2023.

Update: 2 January 2024

I haven’t seen much chatter on the socials over this Office of Management and Budget memo: M-24-08 Strengthening Digital Accessibility and the Management of Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act

Granted, it came out on 21 December 2023, during the holiday crush, and I may not have been paying attention. Anyway, it talks about federal government procurement, training, reporting, AT, policies, etc. and gives timelines for each. I have no insight into the likelihood this guidance will result in change nor if it would survive a new administration (particularly one historically hostile to the disability community).

Update: 8 April 2024

The Justice Department was not the only thing using the moon today to hide something shiny (eclipse joke) — Justice Department to Publish Final Rule to Strengthen Web and Mobile App Access for People with Disabilities announces a final rule under Title II of the ADA. It’s targeted specifically at the web sites and native mobile apps of state and local governments.

Some takeaways from Fact Sheet: New Rule on the Accessibility of Web Content and Mobile Apps Provided by State and Local Governments, lifted verbatim:

- Requirement: The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) Version 2.1, Level AA is the technical standard for state and local governments’ web content and mobile apps.

- Requirement: State and local governments’ web content usually needs to meet WCAG 2.1, Level AA.

- Requirement: State and local governments’ mobile apps usually need to meet WCAG 2.1, Level AA

- Exceptions: In limited situations, some kinds of web content and content in mobile apps do not have to meet WCAG 2.1, Level AA.

- Archived web content

- Preexisting conventional electronic documents

- Content posted by a third party where the third party is not posting due to contractual, licensing, or other arrangements with a public entity

- Individualized documents that are password-protected

- Preexisting social media posts

I am not a (bird) lawyer, so find a qualified attorney (maybe one who does not file SLAPP suits) to answer your questions about how it may impact your government or government-adjacent organization.

Update: 13 April 2024

Overlay frustration

I missed this on the first read through the 300+ page document, but it has a brief statement on overlays:

Several comments expressed concerns about public entities using accessibility overlays and automated checkers.369 This rule sets forth a technical standard for public entities’ web content and mobile apps. The rule does not address the internal policies or procedures that public entities might implement to conform to the technical standard under this rule.

369 See W3C, Overlay Capabilities Inventory: Draft Community Group Report (Feb. 12, 2024), https://a11yedge.github.io/capabilities/ [https://perma.cc/2762-VJEV]; see also W3C, Draft Web Accessibility Evaluation Tools List, https://www.w3.org/WAI/ER/tools/ [https://perma.cc/Q4ME-Q3VW] (last visited Feb. 12, 2024).

The “draft community group report” is from the UserWay-driven W3C Community Group and is in no way a W3C sanctioned document (at least no more than a grocery list).

That Overlay Community Group document definitely did not contain the W3C disclaimer when I looked a couple days ago, nor does it in the most recent version in the Wayback. Eric Eggert filed an issue (#12: Document is misleadingly presenting as an official W3C document) noting this violation of the terms the Community Group agreed to when signing up to use W3C’s hosting. The UserWay rep quickly closed it as “not planned”, but a fix went through in a PR.

I wrote about my concern that the joint UserWay / AudioEye effort using the W3C platform would end up being confused for a real resource (as opposed to astroturfing effort it is), and my concerns were borne out here.

Update: 24 April 2024

The new rule has hit the Federal Register today: Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability; Accessibility of Web Information and Services of State and Local Government Entities. It has 60 days to just sorta hang out, and then it becomes effective on 24 June 2024.

From there, municipalities (not the right word, but I am not a lawyer) with 50,000 or more people have until 24 April 2026 to comply. Under 50,000 have until a year later, 2027.

Also, still not a lawyer. Seek (competent) counsel.

Update: 30 September 2025

When I wrote this post ADA was silent on web accessibility. Then in 2024 the DoJ published a rule under Title II of the ADA making the ADA not-silent on web accessibility.

But in the darkest timeline of 2025, that may be going away. According to the Federal Register, the DoJ is revisiting that decision to reconsider whether some of the regulatory provisions imposed by the April 24, 2024 rule could be made less costly.

When I wrote this post I was not a lawyer. I am still not a lawyer. Ken Nakata is and he wrote about this in DOJ Questioning the New Title II Web Regulation.

I also can’t predict what the upcoming NPRM will say, but, when any administration says that it is trying to make a regulation “less costly,” that ultimately means weakening the regulation.

Sadly, the title of this post may become once again accurate under the current administration.

10 November: Adding Seyfarth Shaw’s take: DOJ To Re-Examine All ADA Title II and III Regulations on a “TBD” Timetable

2 Comments

You made an article claiming ADA isn’t being enforced enough and the laws are vague, implying it only applies to gov services. Yet thousands of small biz are being sued from trolling law firms for said ada compliance. With all due respect, have you been living under a rock? If not, did I just misunderstand this article? I’m a little confused to be honest, since ada compliance is definitely a thing that’s being forced down everyone’s throats, for better or for worse.

In response to . You made an article claiming ADA isn’t being enforced enough…

I did not say that. I quoted a letter from 181 disability organizations asking for

enforceable online accessibility standardsto essentially be rolled into ADA.…and the laws are vague, …

The ADA is vague on online accessibility standards, primarily because it pre-dates the web. This somewhat applies to the others I listed (that are not Section 508 and Air Carrier Access Act).

…implying it only applies to gov services.

I made no implication about the ADA. I explicitly outlined (and linked) Section 504’s and Section 508’s relation to government.

With all due respect, have you been living under a rock?

Yes, it is where the tastiest grubs are stored.

If not, did I just misunderstand this article?

I think so?

To your point, there are indeed a lot of ‘drive-by’ accessibility lawsuits. 60 minutes aired a terrible hit-piece a few years ago. National Federation of the Blind engaged its constituency to identify how this practice harms everyone. Overlay vendors have used this fear in their marketing efforts, even lying about ADA compliance. This is complicated by anecdotal reports that some drive-by serial filers are now looking at sites with overlays, since the overlay vendor may have deeper pockets.

As the opening image demonstrates, I am not a lawyer. However, my general advice is if someone comes seeking financial damages (compensatory or punitive relief) instead of trying to get the barriers addressed (injunctive relief), it is probably frivolous and quality counsel may get it dismissed (which leaves room to maybe recoup attorney fees?).

Prior to a lawsuit, as I outline in my post Sub-$1,000 Web Accessibility Solution, with some small steps you can create an effective bollard should a drive-by filer come your way.

Leave a Comment or Response