Web Sites as ‘Public Accommodation’ under a Pandemic

When an organization receives an accessibility complaint about its web site, a common defense is that there are physical places available for a customer / constituent / user to complete transactions. With a brick-and-mortar available, the web site is simply an added service and so is exempted from Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

To qualify, I am not a lawyer. My notes here are not legal advice, but they are worth considering for the more risk averse.

Title III of the ADA is meant to prevent discrimination based on disability in places of public accommodation, namely businesses that are generally open to the public such as restaurants, movie theaters, banks, schools, and more. It also includes non-residential privately-owned facilities — offices and factories, for example.

In Robles v. Domino’s Pizza, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the web site and app offered by Domino’s are covered by the ADA (January 2019), reversing a lower court ruling. The United States Supreme Court then declined to hear the case, letting the decision stand (October 2019).

Separately, in Martinez v. San Diego County Credit Union the San Diego Superior Court ruled that its web site was not covered by Title III because of the 43 branch locations scattered around the area (February 2019). Leaning on a ruling from Carroll v. Northwest Fed. Credit Union from U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia (August 2018), both cases ruled that web sites do not count as places of public accommodation.

So here is where it gets tricky. If you dodged an accessibility lawsuit because you have physical locations, what does it mean when those physical locations close? What about when the number of locations or the operating hours are reduced?

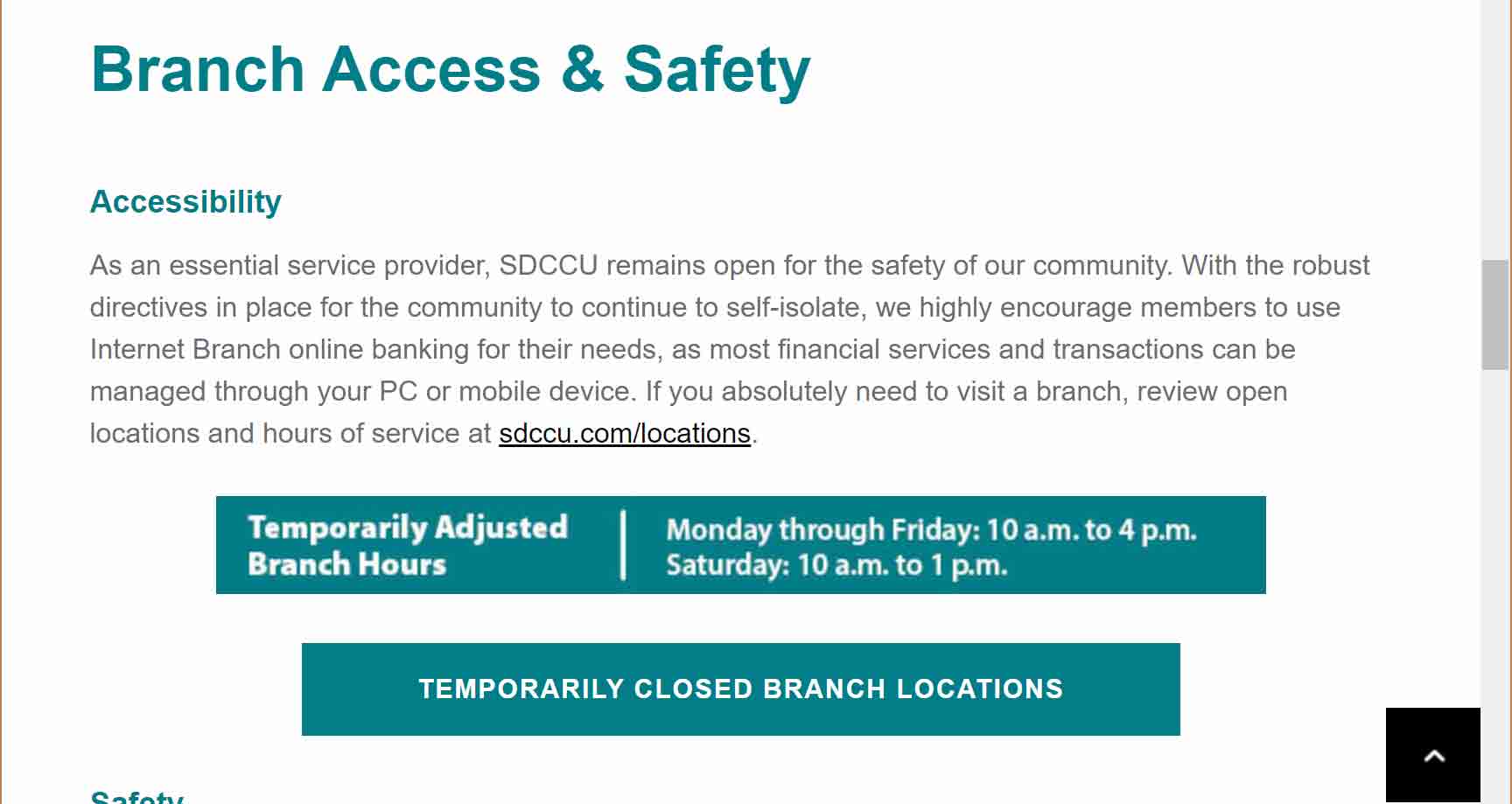

What if that information about reduced hours or locations is available on your web site, which is itself inaccessible, as in this example from the San Diego County Credit Union COVID-19 page?

As movie theaters, restaurant ordering, college courses, and more move to online-first delivery, the notion of a corresponding brick-and-mortar venue falls away. If the current pandemic physical distancing measures stretch into the next year as many think, then this blip becomes the de facto new normal.

I am not suggesting anyone file suits against already-struggling businesses. Lodging a complaint against your local art house cinema or corner deli is a jerk move. But for those businesses who are looking to provide movie streaming services or online menu aggregation, they need to ensure the platforms they are selling to these small businesses are up to task.

For larger organizations such as banks and universities, all those accessibility efforts that were back-burner goals, lost in the backlog, need to be moved up in priority. Any organization that has a risk mitigation mindset should already be ahead of this.

Accessibility practitioners need to convey the real-world impacts on users and customers and help organizations prioritize quick wins for users. Framing the potential lost revenue and bad PR is an option, though per WebAIM’s Hierarchy for Motivating Accessibility Change I would hope we can all find a way to inspire organizations to do the right thing.

At the very least, we all need to make sure the COVID-19 information put out by any and every organization is accessible immediately. Anything else is unacceptable.

Update: 31 January 2021

Ideally a governmental effort to help its citizens get vaccinations would follow some of the accessibility (or even usability) best practices enshrined in its own laws (technology procurement and otherwise). Sadly, that does not seem to be the case. I vented that frustration on Twitter, which follows.

‟What went wrong with America’s $44 million vaccine data system?”

technologyreview.com/2021/01/30/1017086/cdc-44-mi[…]

Deloitte is behind it, and given its history that is part of the problem.

It would be a challenge bridging disparate systems no matter what, though the UI is clearly a major factor here.

For example, when I visit the portal at vams.cdc.gov/vaccineportal/[…], I see the CAPTCHA on the login. I immediately see other accessibility risks.

Then I see holy shit stuff like this:

<a […]="" aria-hidden="true" href="tel:8002324636" class="questionsCall">Call 800-232-4636</a>

That aria-hidden is explicitly hiding the phone number link (and all contact links in the footer) from screen reader users.

Consider lack of headings, lack of landmarks, blocked zoom, and so on, for just the info and login pages, and this is a recipe for disaster.

I see Salesforce’s Lightning Design System is in use (the VAMS favicon is the Salesforce logo, which is awkward).

I have issues with it, but it is evident Deloitte’s devs do not even know how to remediate those issues.

No wonder most at risk audience cannot use this.

Anyway, if I am @CDCgov giving no-bid contracts to @DeloitteHealth, and do not already have WCAG compliance guarantees built in with financial penalties if ignored, I am changing those contracts today.

And if I am @SalesforceDevs, I am trying to get my logo off that site.

As for the states and localities who tried to use @DeloitteUS’s (legally suspect) VAMS platform but then had to build their own due to Deloitte’s malfeasance, I would consider sending the invoices for that work to the federal government to pass along to Deloitte.

Update: 1 March 2021

State web sites are not much better. WebAIM’s WAVE checker found almost 19 errors per page on 81 of 94 state-level sites. Given that WAVE is an automated checker, and given automated checkers detect only about 30% of issues, that suggests potentially 42 more issues each.

WebAIM performed that scan for the Kaiser Health News article Covid Vaccine Websites Violate Disability Laws, Create Inequity for the Blind. Many of them are built on VAMS, the demonstrably inaccessible platform I discuss above. State web sites were not better, however.

For many of the state-level sites that rely on VAMS, this quote stood out in the article:

CDC spokesperson Jasmine Reed said in an email that VAMS is compliant with federal accessibility laws and that the agency requires testing of its services.

When spokespeople gaslight users despite documented evidence and experience, you should not expect things to improve soon.

At Fast Company, 7 tangible ways to make vaccine websites more accessible talks less about accessibility standards, and more about poor language choices, confusing instructions, and failure to consider the technology profile of groups most at risk (elderly and disabled). It offers a good insights even if I don’t necessarily agree with all the advice (do not split the name field into two, but instead renamed it to “Full name” so you do not exclude people who have something other than two names).

Update: 9 November 2021

Lainey Feingold has gathered some recent cases where the Department of Justice has mandated web sites serving COVID vaccine information must be accessible, along with a similar position on kiosks. Read the full details, with links to decisions and agreements in her post Legal Update: U.S. Department of Justice, U.S. Attorneys Offices, Championing Digital Access.

Leave a Comment or Response